This whole question is still a running sore in British politics and culture. A polarising issue in a bitterly divided country. And despite, or maybe because of, Britain leaving the European Union in 2020, there seems little prospect of it going away. Some try to link an anti-European (previously called Euro-sceptic) mindset to a long national tradition, perhaps even to Henry VIII’s 16th century break with Rome. But a short glimpse into the past, and even into quite recent history, shows this to be completely untrue.

Background

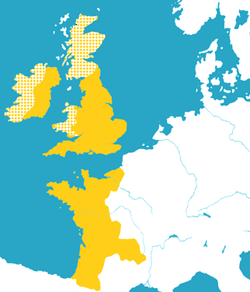

For thousands of years British history has been

closely and intimately involved with Europe. From Roman, Anglo Saxon, Dane and

Norman times England was in Europe, politically, economically and culturally.

Under the Angevins it was joined at the hip to what is now France. In the

Tudor, Stuart and Georgian eras it was always national policy to ally with others

in Europe to stop any single state from achieving European dominance. This

policy ran right through the 19th and 20th centuries against

Napoleonic France and a militaristic Germany. To maintain a balance of power in

Europe was the age old foundation of British foreign policy. But it died overnight

with 2016’s referendum.

For some people, incredibly, the campaigning came down to ‘Britain versus

Europe’. VE Day in May 1945 was to celebrate Victory in Europe, not ‘over Europe’. It’s extraordinary that such a point

should need to be made, but there it is. With such a level of ignorance about

British history, these myths and misperceptions can prove dangerous. It’s an

image of the chap with the Union Jack waistcoat standing on the white cliffs of

Dover shaking his stick at the European continent.

There’s no point trawling the well documented history

of Britain’s European policy. Suffice to say that post war indifference to

formal European ties - the focus was still on a former global role - gave way

as Britain at last decided to join the European Economic Community ‘inner six’.

But two applications in the 1960s were vetoed by French leader de Gaulle. He

thought Britain insufficiently European and too tied to the USA to play a

useful role as an EEC member.

Finally under the Heath Conservative government Britain

joined the Community in 1973, at the same time as Ireland and Denmark. It’s

important to realise the Conservatives were strongly in favour of the EEC, while

anti sentiments were principally on the Labour side, especially among some

trade unions. To deal with Labour divisions PM Wilson held a referendum in 1975.

After some cosmetic steps to ‘renegotiate terms’ the country voted by more than

2:1 to remain. Most of the Cabinet and most Conservatives, including new leader

Margaret Thatcher, campaigned enthusiastically to remain.

Edward Heath with the CDU's Uwe Barschel 1972

Public opinion

From 1975 to 1992 Europe was not usually a major

political issue for the public. PM Thatcher was a driver of the European Single

Market policy. Britain, with its strength in service industries, hugely benefited

from this. But the political extension embodied in the Maastricht Treaty and evolution

into a European Union was being questioned in Britain, despite opt-outs from

some aspects. Populist noises from the UK Independence Party began to echo round

the land.

UKIP was not ‘Eurosceptic’. It demanded Britain leave

the European Union. Its policies were simplistic and rooted in fantasy but it

was noisy and found support in some key parts of the print media. It was also given disproportionate time on Britain’s broadcast TV and radio, notably

the BBC, whose sense of ‘balance’ was to weigh ignorance and nonsense equally with

facts and expertise. It served to legitimise a bad idea that few involved

supported. In the 10 years when the EU and Brexit were regularly debated, the

BBC’s weekly Question Time politics slot had 50 European Parliament members

(MEPs), on its show. Not a single one wanted to remain in the EU. MEP Richard

Corbett observed “British media systematically skewed the coverage of the EU

and dreadfully misrepresented the European Parliament”.

UKIP had no MPs. But in the 1990s it gradually picked

up mainly Conservative votes in local and European elections. Fearing Tory

votes were leaching to UKIP and to try and avoid a party split, PM David Cameron

sought to repeat Wilson’s 1975 plan - ‘renegotiation’ and a referendum. This

was designed to fix his political problem and few observers believed he would

lose it. With the 2015 election a referendum became firm policy and seemed to carry

general support.

For a long time polls had been showing the European issue

was way down the list of priorities for most people. Typically, through the

1990s to 2010 only 5% or so claimed in opinion polls that Europe was the most

important political question for them. It only became a burning issue

nationally when Cameron promised to hold the ‘in/out referendum’ before 2017. The

key Brexit theme among its supporters seemed to be ‘British exceptionalism’,

the idea that Britain and its people were better than others and had no need to

join any systems of rules.The country had always done ok in the past alone and

would do again in the future. This was grabbed and intensified by the tabloid

press, mainly owned and controlled by overseas-based tax exiles.

Crooked referendum

Lies, disinformation and illegitimate, hard to trace

overseas money were a big part of the referendum process. Most of the Cabinet

still campaigned to remain, with some key exceptions, though Labour’s

unconvincing and ambiguous leader was very unhelpful to the Remain side. Yet

Parliament supported the call for a referendum across the political spectrum. The

vote might have stipulated a minimum 60% majority threshold, as do most

constitutional changes, but it was left at a straight 50%. The result was a

52%-48% bare majority to leave.

The Conservative Party then virtually became UKIP in a

matter of two years. It is a remarkable and unprecedented move, still barely

understood, UKIP entryists effectively took over many of the local Conservative

associations and virtually all pro-European MPs were forced out or decided not

to stay. It amounted to a coup in all but name. The character of UK politics

fundamentally changed overnight. And a winner take all ‘hard Brexit’ followed.

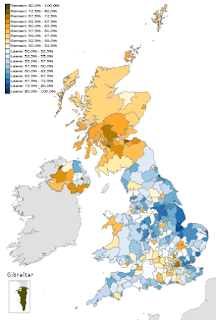

Why the vote? It seems Leave support had little to do

with economics. It’s perhaps too early for definitive explanations but research

shows anti EU sentiment was strongest among older, socially and culturally

conservative people worried about change. Immigration concerns were key as sometimes, was simple racism. In post referendum research, the correlation with

authoritarian attitudes wanting simple solutions to problems - death penalty,

child discipline, LGBT rights - was marked. There was also a large education

divide - 70% of those with higher education voted to remain. The less educated

voted strongly to leave.

Turkeys voting for Christmas

The combination of an aging population, economic

dislocation from globalisation and deep social anxiety, with fears about

immigration, proved enough. The people involved thought they had it better in the

past. But as former Chancellor Philip Hammond insisted, this is the group who

will be hardest hit by the changes. Indeed the evidence so far with 'supply chain problems' seems to bear this out.

Vox pops on the Leave side were unedifying. “It’s what

we voted for - we want it because we want it!” A curious, rather childish sort

of psychology. Nobody has come up with any benefit from leaving the EU, a

monumental self-disabling trauma. It affects trade, international services,

farming, security and pretty well every aspect of British life. To give an idea

of its importance, when Britain joined the EEC in 1973 the country’s total

international trade (exports and imports) was under a quarter of real GDP. By

2018 that proportion had risen hugely to nearly two thirds. The government's own figures

project a cut in GDP of 4% - a huge decline in Britain’s living

standards, setting aside extra invisible costs. There’s just no point in it.

It’s worth highlighting that several other countries

have had anti EU referenda results from time to time, after similar populist

pressures. But they always managed to reverse such decisions with more accurate

information than simple slogans like ‘Take Back Control’ and ‘Get Brexit Done’,

when wiser counsels were allowed to prevail. In fact there were some huge public

marches and demonstrations in London - at six million people the biggest ever seen - and petitions

signed by several millions of people

demanding a Brexit re-think via a confirmatory referendum. These were turned

down by the government, dominated by the extremist, referendum inspired, VoteLeave

political and financial pressure group.

Recent 2021 polls showed only a minority - 30% and as low as 18% - of people still thought the Brexit decision was the right one. But that

ship has sailed. Excluded from the EU single market and customs union no one convincingly

claims any real benefits from a UK departure. State security organisations hinted

that with dark money and misuse of data Britain was suckered into the vote to

leave - but people don’t want to be told this. The influence of opaquely

funded ‘think tanks’ trying to create an offshore archipelago of deregulated

dark money is hard for people to understand. In any case too many of those in

and around government were involved for any action to be taken.

Says polling expert Peter Kellner on the Brexit vote,

“Commanding that relationship to end and expecting not to suffer is as futile

as commanding the waves to stop and expecting not to get wet. Britain is now discovering

the dismal reality of ‘taking back control”. The EU-UK Trade and Co-operation Treaty of December 2020 effectively secured EU dominance in trade over Britain,

and opened the door to increased EU access to areas like financial services

where Britain has been strong and has run a large surplus. As a ‘rule taker’

Britain has no power in setting commercial and trading regulations. With

the likely crumbling of both pillars of British foreign and security policy -

Europe and the United States - the overall costs to the country from this

self-harm, including the loss of influence and prestige, are truly

incalculable.

Long nightmare

As conservative historian and editor Max Hastings said, “The issue of Europe has not merely poisoned Britain’s politics, but

induced a drugged stupor in many of its people. They have embraced a nostalgic

vision that some of us fear will deny us a stake in the most important and

exciting things the world will achieve in the years ahead. We have voted to

become a theme park”. In fact everyone cherishes sovereignty, but the British approach is outdated and simplistic. The world's problems - from climate change to security, from Covid-19 type pandemics to international terrorism - are now multilateral.

No comments:

Post a Comment