In 1985 American educationalist Dr. Neil Postman

published a book, “Amusing Ourselves to

Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business”. He said that today owed

more to Huxley’s Brave New World, with

people addicted to amusement, than to Orwell’s vision of public state control. Citizens’ rights were now exchanged for entertainment. TV news is “misplaced, irrelevant, fragmented or superficial information

that creates the illusion of knowing something”, wrote Postman.

If anything this view has proved even more prescient in the 35 years or so since. These days, it seems, public interest in political,

social and economic issues can only be sustained through media celebs and TV

‘personalities’. Leaders are chosen and gain electoral success just by being

recognisable from their media exposure. The key quality is visibility, with a gift for the

photo-op. And many people only look that far, if indeed they notice politics at

all. As former Chancellor Ken Clarke said recently, “There is an increasing

yearning for colourful theatrical personalities with simple solutions to

complex problems. These individuals offer up scape-goats and easy ways out that

save people from having to engage with a very confusing world”.

The Brexit disaster

This has reinforced the trend to populist politics and

politicians. Eight years ago, in an attempt to appease one faction of the

Conservative Party, a fateful decision was taken. Though Europe hardly figured

in wider public priorities at the time, PM Cameron decided if his party won the

election there would be a simple in out referendum on the UK’s membership of

the European Union. The vote, and subsequent Brexit, has seen Britain decline

from a successful, open outward-looking state, with good co-operative relations

with Europe and the globe generally. It’s now economically and politically

weak, angry with itself and pitied by the rest of the world. Some say a state nearing its own dissolution.

So what are the myths leading the country to

this monumental act of self-harm? First the idea that Britain was being held back

by an endless plethora of rules decided by the European Union, that if only the

country could escape from, we’d all be better off. A ridiculous idea, of

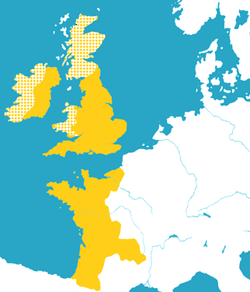

course. Britain had key opt outs as an EU member, including Schengen, and avoided joining the Euro. In fact the country had the best of all worlds with

its whole economy - and financial services particularly - benefiting from the

Single Market.

Populist myths

Extending the myths, those who led the Brexit charge

promised ‘we’d take back control of our laws, our money and our borders’. But ‘we’

already had control of them. When shortened to ‘take back control’ it could

mean absolutely anything. Like many such slogans, it offered an apparently

simple answer to complex problems in an increasingly complex world. It appealed

to the credulous, the angry and the disappointed. It was backed by tax exiles.

And the list of broken promises is endless. Most notable was the wealth the

country would gain (the government itself now predicts a major decline in GDP).

Former Deputy PM Michael Heseltine said, “Just take

the phrase ‘Take Back Control’…The government is lurching from crisis to

crisis, and it’s patently not in control”. Writer Nick Tyrone asserts, “Brexit

was a revolution disguised by its champions as a minor change, all to free the

country from an oppression that was always entirely imaginary, as well as to

try and take advantage of opportunities that do not actually exist”. An absurd

but recurrent belief among Brexiters is that any problem can be solved if the

rest of the world would just reorganise itself to fit in with Britain.

Brexit was clearly based on a series of myths

swallowed by enough people to force the issue. And

despite a near 50:50 split in the 2016 referendum it has been delivered in a

‘hard‘, ideological version. Given the accompanying lies, its supporters have

felt obliged to keep up the fantasies. Worse, under cover of the Covid-19

pandemic and Brexit, PM Johnson’s government is steadily weakening the constitutional

props and institutions defining a liberal democracy. Sometimes dressed as emergency

measures, Britain is being remade along populist authoritarian right wing lines.

Shafting Britain's constitution

The sovereignty of Parliament and the rule of law are Britain’s

constitutional keystones. Yet in 2019 Parliament was illegally suspended. There

are plans to make judicial review harder, with the Law Society warning of a

threat to curbs on ‘the might of the state’. The PM wants power to override judges. New laws against public protests,

whistle blowers, government accountability, plus widening the scope of the

Official Secrets Act are in preparation. The government threatens the

independent Elections Commission, and new voter ID moves will hit those with no

driving licence or passport. It wants to hobble bodies that may restrain the

state, and to replace the Human Rights Act. It flouts laws and conventions at will - all to keep a grip on power. But threats to the Northern Ireland Protocol inspired European, and particularly US, pushback.

The process of debating and approving measures in Parliament

is being regularly by-passed by ministers. There is little, if any

parliamentary scrutiny. This worries growing numbers of informed people,

including Sir Jonathan Jones, former head of the Government Legal Department.

The ministerial code governing behaviour, and aiming to avoid corruption, is

regularly broken. There’s no longer any independent adjudication. When Home

Secretary Patel was earlier found to have breached the code there were no consequences and the matter was just

dismissed.

All this is not normal. It can’t be treated as just politics as usual. Cabinet and

parliamentary government now barely exists. A small group of ‘courtiers’

surrounds Johnson, picked not for competence but loyalty to him and the Brexit

lie. In the past if a minister lied in Parliament he had no choice but to

resign. But Johnson and his colleagues lie prodigiously as a matter of choice. It’s

worth stressing that this is not the Conservative party of old. Many of those members with moderate views and government experience were forced or eased out.

Entryists from UKIP helped take control of several constituencies and some of

these people are now serving ministers. The Conservatives have largely been transformed

into populist UKIP-lite English Nationalists.

Threat to democracy

It’s said that Britain’s constitution depended on

people being ‘good chaps’. That with a covenant of mutual tolerance politicians

would abide by unwritten rules and conventions. And until now, they mostly have.

But when people who are not ‘good chaps’ take power, the fragile fabric is easily

broken. Would a written constitution help? It’s worth noting that the USSR

constitution was perfectly democratic in theory, but cruelly authoritarian in

practice. And the USA still suffers huge gun violence dating from the right to use muskets in a

rural 18th century society. Perhaps a Bill of Rights would help, but

there’s no easy answer.

Coups may occur without a bunch of colonels moving their tanks into the capital. Britain’s

democracy is barely 90 years old, or only 75 if we ignore the national

governments of World War II and the 1930s. H.A.L. Fisher in 1935 said, “Progress

is not a law of nature. The ground gained by one generation may be lost by the

next”. Historian Rob Saunders points out, “The first UK prime minister born under

universal suffrage was John Major. Every PM from Baldwin to Thatcher saw

democracies collapse or be crushed. That democracy is fragile is a lesson we

forget at our peril”.

Corruption

Brexiters condemned endemic corruption in the EU. They

promoted the myth that leaving would shield the UK against such taints. Instead

the combination of Brexit and Covid-19 has given opportunities for a huge level of corruption in Britain. Establishing so called VIP lanes for procurement of personal

protection equipment and testing capacity has resulted in around 50 companies

awarded contracts without competitive tender. Many had no experience or

competence in the field, though they had links with ministers or Conservative

party donors. In one example 43,000 people were wrongly given a negative Covid test result. The sums involved are enormous - over £12bn.

Legal challenges are proceeding against the

government. The Major administration of the mid 1990s was crippled by sleaze,

and the ‘cash for questions’ scandal. This pattern has returned but at a turbocharged level. Eye watering sums have been uncovered in paid consultancy

lobbying by some MPs, completely against the rules. Several ministers and ex

ministers have been implicated, too. The consequences have yet to be seen.

For anyone who didn’t realise, it’s abundantly

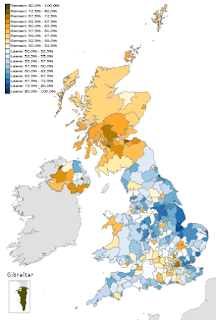

clear that Brexit is a disaster. Nobody can cite one single benefit to Britain. Fewer and fewer people in recent polls now think leaving the EU was the right

choice. The number should fall even further as the effects become

clearer and Britain’s overall position deteriorates. The government keeps

repeating the lies rather than face up to the truth. But once lies start they

have to be kept going. It seems just too difficult politically to admit that the

emperor has no clothes.

Ameliorating the damage

So how to get out of the mess? Many find it hard to

admit they were conned or foolish in supporting Brexit. In 2017 the security

services concluded in private that the public had been shafted. Still, common sense and geography should dictate change. It’s impossible for Britain to re-join the European Union soon.

But a step by step approach may help. First is to try and rebuild damaged relations

with Ireland and the EU. Then Britain could cooperate with Europe on things

like Erasmus and standards alignment with further moves to ease friction

on trade and other areas of mutual interest. Gradually a more positive climate may

emerge. No-one needs to admit folly. It gets everyone off the hook. But a change of PM is a sine qua non here.

Meanwhile culture wars are a key part of Johnson’s divide and

rule modus operandi. He has a group in Downing St stirring this pot - involving

statues, misinterpreting history, music - indeed anything the media can work

into a national dust up. Other japes are akin to putting up a two fingered

salute to foreigners, especially if deemed to be part of the ‘liberal elite’. Straight

out of the Trump playbook. But it's not clear this is really effective.The culture war extends to Covid-19 too. The ‘libertarian’ wing of the Tory party recently had 100 MPs rebel against their own government on new pandemic safety measures.

A more familiar pattern returned as the Tories lost a solid seat in a by-election with a swing of 34% against them. Polls confirmed Johnson’s public popularity rating was at its lowest ever level. Ministerial Xmas parties during the pandemic, when the public were bound by strict safety measures, cut through and hugely damaged him. On 12th December 2021 Sunday broadsheet ‘The Observer’ wrote: “It is a national misfortune that we have a man who is by far and away the worst post war prime minister in office at the time of the worst post war crisis. Johnson lacks any shred of integrity, is driven by ego and self interest, and has been prepared to mislead voters again and again. He is incompetent and embodies the entitled politician who sees politics as a game rather than a duty. He is utterly unfit to govern Britain” This view was common among former Conservative colleagues.

The future?

This is the final chapter of my blog. In a

previous post I quoted Dean Acheson’s 1962 remark “Britain has lost an empire and

not yet found a role”. But it did develop

a role, as a key member of the European Union. And a doorway to Europe for the

United States. Offering a sound trading environment for Britain, recognising the UK's strength in financial services, the EU was a realistic and helpful political option for a medium sized, respected state.

Throughout its history Britain has overcome problems and mis-steps, many of its own making. But in 2016’s ill-fated

referendum, a combination of lies, dark money from overseas and shocking media

behaviour, lured the country into a mythical fantasy of past glory. Emotional, not rational, this disastrous choice began a sad period for Britain. Russian money was very likely involved. The former Russian ambassador actually claimed his country had got what it wanted. A modern democratic state has been all but taken over by a small group of extremists 'gaming the system' of lax media rules, with weak constitutional laws and conventions. All of Britain's authoritarian populism and corruption has resulted directly from

it. Our history is respected. But it’s a hard road to a more hopeful horizon.