‘If you remember the sixties you weren’t there’ as the phrase goes. Nonsense, of course, and the whole subject is full of such myths and misconceptions. But it was still a period that saw an undeniable wave in Britain, with a big shift in cultural values backed by political and social change. The country experienced a revolution in design, art, music, film and fashion - new service industries making London a leading cultural centre and a magnet for talent from all over the world.

But let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. It

was, at least at first, a strongly London based wave. Time magazine seems to

have coined the idea with its 15th April 1966 cover “The Swinging

City”. A piece in that issue proclaimed, “In a decade dominated by youth,

London has burst into bloom. It swings; it is the scene” - the Swinging label was

born.

The sixties in memory

For many people, the sixties remain a fond memory. On the surface they think of the fashions, ‘sex, drugs and rock and roll’, the radicalism of pop culture and the freedom of a more permissive society. As Philip Larkin jokily put it, “Sexual intercourse began in 1963 (which was rather late for me) - Between the end of the Chatterley ban and the Beatles’ first LP”. Others will see it as a progressive and more tolerant era of social reform and even transformation, with the end of the death penalty, liberalisation of homosexual and abortion laws, a lower voting age and weakening of class divisions. Politically the 60s was animated by human rights, Anti-Apartheid, and the fallout from 1962’s Cuban Missile Crisis.

For yet others, including many of a more traditional

mindset, it was the opposite. Establishment values were mocked and satirised,

and the roles of family life, authority and religion questioned. Opponents of

this new culture were discomfited and saw the start of what was a less hierarchical

and deferential age as the end of the world as they knew it. The 60s was a

period of moral decline, they believed, the time the rot set in.

Culural and social reality?

The ‘sixties’ as a phase really did begin in 1963. It was when PM

Macmillan resigned, after a scandal involving Jack Profumo, a government

minister, and good time girl, Christine Keeler. As it involved a Soviet spy and

aristocratic names, it was a tabloid dream. But it exemplified the start of an

inter-generational culture war. In 1964 a

Labour government was elected and provided a political base for the social

changes to come.

Dominic Sandbrook has cleverly pointed out in his Never Had It So Good the numerous myths

and misconceptions about the era. At the time of such musical innovators as the

Beatles, who carried fans with them through the 60s on a long, ever changing

creative journey, South Pacific was

the top selling record album for 46 weeks. Two versions of The Sound of Music occupied the charts for five years. 20 million

regularly tuned in to watch The Black and

White Minstrel Show on TV. Mmm - little evidence of an appetite for

creative innovation there.

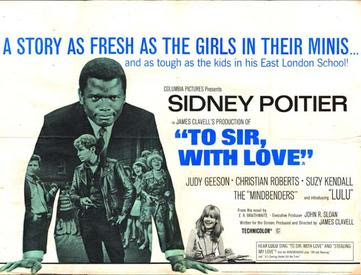

Miniskirts were a key image of the times but outside

London they were slow to catch on. And by the end of the 60s only one in ten women

had used the contraceptive pill. In 1964 most teenagers were virgins at 19.

Feminism, and its media creation ‘women’s lib’ did not take hold until the 70s,

10 years later. While this 60s period was arguably the first time people in the

working class had money and a degree of cultural respect, they retained a

largely conservative outlook. In 1969 polls showed most Britons wanted to

restore capital and corporal punishment, and 80% supported making smoking

cannabis a crime. It hardly suggests a liberal and tolerant public mood.

Facts and figures

The key dates in the decade were perhaps 1964, with a

new Labour government and the Beatles’ musical breakthrough, and 1966, when

England won the World Cup at Wembley. 1967’s Summer of Love is often recalled

in hindsight, but was maybe more of an American than a British phenomenon. The

devaluation of the pound in 1967 seemed a major event at the time, too, if not today.

Less remembered is the inaugural Concorde flight in 1969, the result of a major

Anglo French aerospace project. It encouraged a feeling of European

co-operation.

Whatever the generation or sub-culture, the 60s was certainly a time of growing prosperity. The proportion of owner-occupied homes rose from 41% at the start of the 60s to nearly 50% at the end. In 1960 only a third of households owned a car but by 1970 nearly 50% owned one or more cars. Motorway building to accommodate these extra vehicles was a feature of the 60s. Disposal income became a reality for many people and they chose to spend much of it on services - entertainment, sports, foreign holidays - and not simply on ‘things with plugs on’.

London effect

Clearly some pre-conceived notions about the 60s are

wrong, as Dominic Sandbrook points out. For most people outside London life and

attitudes went on much as ever. Unless you were a rock star it wasn’t easy for

young people to acquire cocaine, cannabis and LSD as is sometimes supposed.

Films and TV drama may have fostered images of sexual freedom but social

research suggested most men just wanted their women keeping house and raising

children.

So where does the truth lie? There's no doubt that

traditional values were rejected by a large minority of young people,

particularly in London. And there is clearly a progressive legacy from the 60s

of social reform and tolerance enshrined in law. But the leaders of this

culture or ‘influencers’ as they might now be called, were labelled insidious

radicals causing huge damage to the accepted order.

Reconciling progress and tradition

Sociologist Frank Furedi has shown that there had been

a general lack of intellectual thinking about how a society with rising

prosperity could accommodate and reconcile authority, family life and religion.

These questions were not really answered. In this vacuum a handy media-packaged

idea of ‘The Permissive Society’ was justification, explanation and scapegoat

for left and right thinkers alike.

On today’s intellectual confusions, Furedi writes,

“The 1960s did not create these problems. Indeed one of the positive

consequences of that period was that it brought the intellectual and moral

crisis of modern society out into the open…The authoritarian imagination

confuses permissiveness with the prevailing climate of non-judgmentalism.

Permissiveness is a precondition for a truly tolerant society, but tolerance

should not mean a reluctance to make moral judgements or to take strong stands

against forms of behaviour deemed wrong”.

No comments:

Post a Comment